Covid-19 has forced governments and healthcare workers around the world to make difficult and painful decisions about whose care to prioritise and how. Arts and Humanities researchers provide vital insight and scrutiny into the ethical dimensions of these decisions. In this blog post Dr Vivek Bhatt, Postdoctoral Research Associate for the AHRC-funded project ‘Ensuring Respect for Human Rights in Locked-Down Care Homes’, outlines some of the findings of the Essex Autonomy Project’s work investigating triaging decisions from the perspective of human rights.

By Dr Vivek Bhatt, 10th May 2021

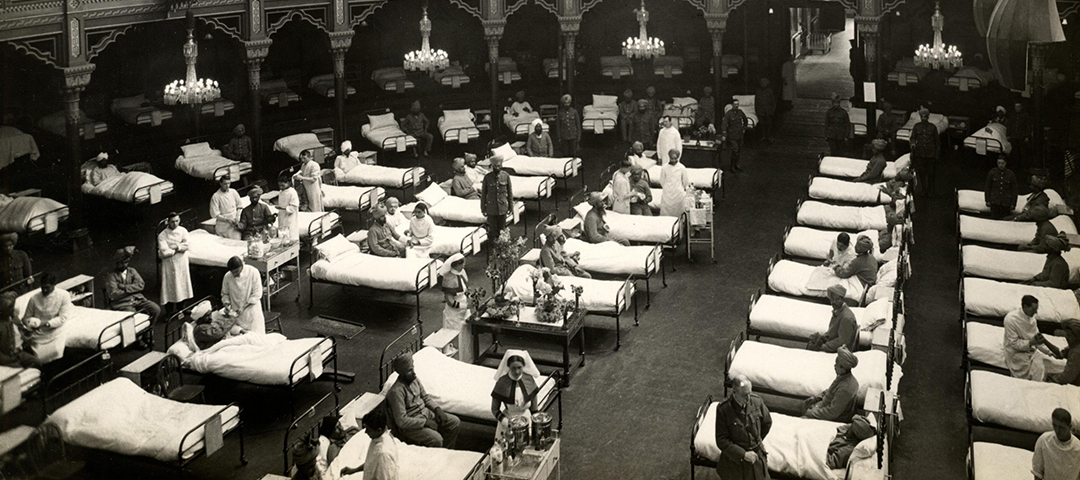

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen many hospitals around the world run out of ICU beds and critical supplies such as oxygen, with frontline workers forced to decide who should be prioritised for potentially life-saving treatment. This decision-making process is referred to as ‘triage.’ The practice of triage began during the Napoleonic wars and developed further during the two world wars, with the implementation of systems for sorting and prioritising wounded soldiers for treatment. As recent events have shown, triage decisions are equally difficult, and just as often painstaking, in the context of COVID-19. In Ontario, Canada, a spike in ICU admissions for COVID-19 treatment may soon force doctors to activate triage policies that provide a matrix for deciding who should be allocated the few remaining ICU beds in the province. And hospitals in India, where oxygen is in short supply, have set up ‘war rooms’ in which clinicians try to decide who should be prioritised for ventilation.

Cases, deaths, and hospital admissions are now dropping in the UK, but scientists warn that a ‘third wave’ may occur as early as summer 2021, especially if international travel resumes later this month and vaccine-resistant variants become more prevalent. It remains possible that intensive care units in the UK will be overwhelmed by a surge in COVID-19 infections. And the question of how frontline workers should make triage decisions remains unanswered. In February 2021, a number of families affected by the pandemic went before the UK Administrative Court to argue that the Government had acted ‘irrationally’ by failing to implement national triage guidelines. This argument was rejected by Justice Swift, who noted that development of a national triage policy would be controversial, difficult, and likely to result in inappropriate decisions in individual cases.

In the absence of any national guidelines, local hospital ethics committees across the NHS have found themselves developing their own triage policies. A discussion paper written by doctors and lawyers at the Royal United Hospital Bath NHS Trust contemplates the contents of such a policy. The document, which I shall refer to as ‘the Bath protocol’, suggests that triage decisions should be based upon patient and family consultation, clinical assessment, and a range of ethical considerations. These ethical considerations are geared towards the realisation of an overarching goal: ‘to save more lives and more years of life.’

Scholars at the Essex Autonomy Project, which has also received AHRC Covid-19 funding to investigate the issue of human rights in care homes, have recently published an article in response to the Bath protocol. The article argues that, when put into practice, the ethical framework presented in the Bath protocol is likely to result in irresolvable dilemmas. Imagine, for example, a situation in which a 28-year-old and 50-year-old present with acute illness resulting from Covid-19. Both require critical care, but hospital services are overwhelmed, and doctors must decide who to prioritise for treatment. The ethical directive of saving ‘more years of life’ is likely to result in the prioritisation of the 28-year-old. But the severity of illness suffered by that patient, or other pre-existing health factors, might mean that he or she needs to be in intensive care for much longer than the older patient who was denied critical care. The longer an intensive care unit is at capacity, the higher the number of other patients who might not be admitted. So, in this situation, saving ‘more years of life’ has prevented the fulfilment of the other half of the ethical imperative presented in the Bath protocol: saving more lives. Noting the likelihood of such dilemmas arising from the triage decision-making process, the authors suggest that the discipline of human rights provides an essential supplement to the framework set out in the Bath protocol.

Two human rights principles are particularly relevant to triage decisions: non-discrimination and the equal dignity and worth of every human being. These principles are at the core of the international human rights movement, and they are enshrined in the NHS constitution. While triage decisions pursue the goal of saving lives, they must be sensitive to these core human rights principles. Some of the ethical criteria set out in the Bath protocol are unlikely to pass the tests of legitimacy, necessity, and proportionality, which are used by courts to determine whether a measure that interferes with human rights is lawful. Take, for example, the goal of ‘saving more years of life.’ This is distinct from a directly discriminatory policy of denying critical care to those over a certain age, as was considered in Italy early in the pandemic. But a triage decision based upon a patient’s projected lifespan may be indirectly discriminatory, because it is likely to result in the denial of critical care to older people and persons with disabilities. A policy of saving those who have the longest left to live also contradicts the principle that every human being is of equal dignity and worth. Why are the lives of the elderly and disabled of any less worth than the lives of the young and healthy?

The article by University of Essex scholars thus calls for the integration of human rights considerations into hospital triage policies. Any approach to the allocation of scarce critical care resources must be subject to strict scrutiny in relation to the applicable human rights standards. And as decision-makers continue to prepare for future waves of COVID-19 infections, or future pandemics, they should engage in interdisciplinary dialogue with clinicians, legal practitioners, and human rights experts alike.

Dr Vivek Bhatt is a researcher and teacher of human rights, international law, and politics, and is Postdoctoral Research Associate for the AHRC-funded project, ‘Ensuring Respect for Human Rights in Locked-Down Care Homes’, at the Essex Autonomy Project (Grant number: AH/V012770/1). Vivek’s research focuses on the human rights dimensions of COVID-related decision-making in UK care homes and intensive care, with particular emphasis upon the right to life and the prohibition of discrimination.

You can find out more about the Essex Autonomy Project here, and you can read about other AHRC Covid-19 projects working on the ethical challenges of the pandemic here.