Professor David Tollerton has led on National Day of Reflection and the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from past memorialisation. Here, he shares some findings from his report into COVID-19 memorialisation, which was published last week.

The global COVID-19 pandemic is an event of immense scale in terms of loss of life and societal impacts. But once it is over, it will not simply sit in history making its meanings self-apparent. The extent to which remembrance gains traction in public consciousness, and the narratives infused with such remembrance, will be complex, contested, and evolving. It is a story beginning even before the pandemic has ended, with numerous memorialisation initiatives already established. 23 March, for example, will mark Britain’s second National Day of Reflection. Marie Curie led the original campaign for the day, and since February 2021 I have worked with them on an AHRC project examining emerging British remembrance of the pandemic. The final 56-page public report from the project has just been published by the University of Exeter. Based on a series of workshops and interviews, it found that a vast array of practices are emerging into a situation of overall flux regarding questions of what we are remembering and why, who should organise such initiatives, and how they should be framed. Being critically aware of such dynamics is of crucial importance for how society publically comes to terms with the pandemic.

The question of what is being remembered, and why, might initially seem like a strange one to ask, especially for those grieving the loss of those close to them. But it becomes vital when you start to think about the differences of how narrowly or broadly we understand the scope of remembrance. At the National Covid Memorial Wall in central London, the focus is on those who died from having contracted the virus, with each red heart representing a single individual with COVID-19 on their death certificate. At events and sites organised by Covid19 Families UK, Forest of Memories, and St Paul’s Cathedral’s ‘Remember Me’ project, a broader view is taken in terms of memorialising all deaths since March 2020, particularly with an eye to those who faced social distancing regulations that disrupted funerals and grieving processes. For Marie Curie, the National Day of Reflection is intended to have a similar scope, though others have understood its purpose in even broader terms. During the first National Day of Reflection, in March 2021, some looked also to the plight of those suffering from Long Covid, while the Prime Minister, in his official message of support, sought to draw attention toward the wider work of the NHS, vaccine development, and public efforts to reduce transmission. Perhaps, we might conclude, what is needed is a mode of remembrance that draws in all of society’s pandemic experiences, including challenges concerning mental health, homelessness, child development, domestic abuse, and economic hardship. And yet the fear, explicitly voiced by interview participants for this project, is that the specific experiences of death and bereavement might be lost amidst such a generalised approach.

Alongside such variations of scope we also necessarily need to address variations of purpose in setting up public remembrance practices. The hashtag for last year’s National Day of Reflection was #uniteinmemory, and we might view public memory as a means of promoting solidarity through the sharing of collective experience. But alongside this, others have suggested that we need to actively remember the diversity of how people were impacted by the event. The Majonzi Fund has been set up to specifically support memorialisation among BAME communities, referencing the extent to which rates of death have been notably higher among ethnic minorities (an issue that in turn points to wider systemic inequalities).

A different risk with emphasising remembrance as a force for unity is that it may encourage a disproportionate focus on ideas of sacrifice and national overcoming, to the expense of primarily mourning loss. When Boris Johnson endorsed the 2021 National Day of Reflection he sought to play up ‘the great spirit shown by our nation’ and some local memorial projects have attempted to combine mourning with the celebration of achievement during the pandemic. Not all are comfortable with such positioning, fearing that language of sacrifice and overcoming might be appealing to politicians and the wider public, but can distract from both supporting the bereaved and asking hard questions about why so many died from COVID-19.

As well as instabilities in the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of public remembrance, there is also a contested debate on who should lead the establishment of memorial initiatives. In relation to other historical events, the state has often played a key role in orchestrating commemoration, and in May 2021, Boris Johnson in turn announced that a UK Commission on COVID Commemoration would be launched. But no detail about the commission has subsequently emerged, and when conducting interviews with grassroots remembrance organisers many were sceptical about whether the UK government could lead on this given the questions about its performance during the pandemic. In the media, several commentators have been equally scathing, and it is difficult to see how such top-down remembrance could be uncontroversial. In the absence of activity from the UK government, a wide variety of grassroots initiatives have come to the fore, and while Westminister-led plans have been muted, regional governments less tarnished with accusations of mismanagement and ‘partygate’ have played more of a role. The Scottish government, for example, has announced that it will actively support ‘Remembering Together’, a programme which collaborates with local authorities and creative artists ‘to remember and honour all those affected by Covid’.

Questions of who leads remembrance also extends down to the level of individuals and their variations of identity. One of the unexpected findings of the project was that digital remembrance initiatives – specifically those associated with Covid19 Families UK, St Paul’s Cathedral’s ‘Remember Me’, and Yellow Hearts to Remember – have featured a discernible gender imbalance, with women participating more than men. Perhaps one challenge for the future will be to find ways of framing remembrance that facilitate and support modes of grieving and reflection among men. The project also found that, in some cases, public remembrance also intersected with issues of religious identity. St Paul’s Cathedral’s plan to build a physical memorial has been endorsed by the UK government and described by its media supporters as a ‘national memorial’, but it’s location within specifically Christian space raises questions about inclusivity (however earnestly its organisers have invited participation from non-Christians). It is notable that during the 2021 National Day of Reflection the BBC deferred to Christian clergy during coverage of its more meditative moments, and so we might wonder whether the state broadcaster was slipping into a culturally familiar – but questionably inclusive – model of communicating collective grief.

A final consideration is the ‘how’ of public remembrance. As the first global pandemic of the digital age, it is unsurprising that amidst social distancing restrictions a variety of early remembrance initiatives sought to share experiences of loss online. But over time it has become apparent that there remains an underlying human need for reflective spaces and in-person events. These have developed into a dizzying array of memorial forms: gardens,trails, hillside sculptures, statues, walls, pillars, hand-painted pebbles embedded into public spaces, lantern parades, and candlelit vigils. Several major initiatives combine the physical and the digital, with Forest of Memories, for example, aiming to establish numerous memorial woodlands in which visitors can use their handheld devices to link each planted tree to the story of an individual life lost.

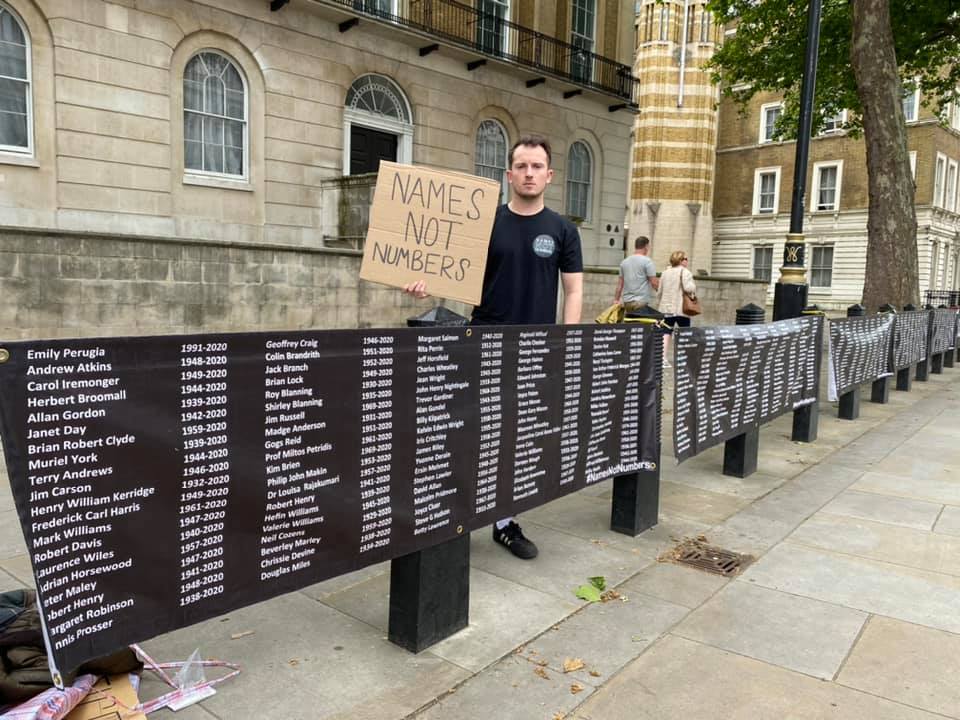

Spanning all initiatives has been the challenge to communicate both the scale of loss and remembrance of individual experiences. In interviews, many organisers voiced dissatisfaction with the government and media presenting statistics of death that they felt depersonalised loss. The Names Not Numbers group staged street memorial-protests because of this very issue, producing vast banners that listed some of those killed by the virus, while the National Covid Memorial Wall – pointedly located opposite the Houses of Parliament – combines imposing physical size (it takes some 10 minutes to walk along at normal speed) with each painted red heart representing an individual lost.

In facing this question of how to represent scale but avoid depersonalisation we encounter an issue that has been similarly encountered in remembrance of other historical events. With regard to Holocaust memory, for example, at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., visitors are each issued with an ‘identification card’ that provides details about a single individual persecuted in the Holocaust, while in continental Europe over 70,000 inscribed stolpersteine (‘stumbling stones’) have been laid outside the former residences of victims. There is a broader point here that when considering all of the issues noted above it is useful to bear in mind resonances with other memory cultures, both in terms of the challenges they have faced and the strategies they have developed. In the public report from this AHRC project, particular attention is given to remembrance of the First World War, the 1918-19 Influenza pandemic, and the Holocaust, but responses to numerous other historical events might be cited.

Several of the organisers interviewed for this project acknowledged that, in practice, we must allow public remembrance of the COVID-19 pandemic to develop organically. We might conclude that we need to just accept the current state of flux and be reconciled with uncertainty about how society’s consciousness of the event evolves. But as the second National Day of Reflection approaches, it is also useful to ask how we might encourage productive debate and develop ‘better’ forms of public memory (however ‘better’ is construed). What should the scope of remembrance be? Which narratives of the pandemic’s meaning are more valuable or problematic? How do we recognise the diversity of experiences and their intersection with matters of identity? What are the best modes of facilitating public remembrance? And how do we convey a sense of scale but remember the individual lives lost since March 2020? The answers to such questions should not be understood as self-evident or uncontested. The hope of this project and its final report is to provide one tool that feeds into such necessary debate.