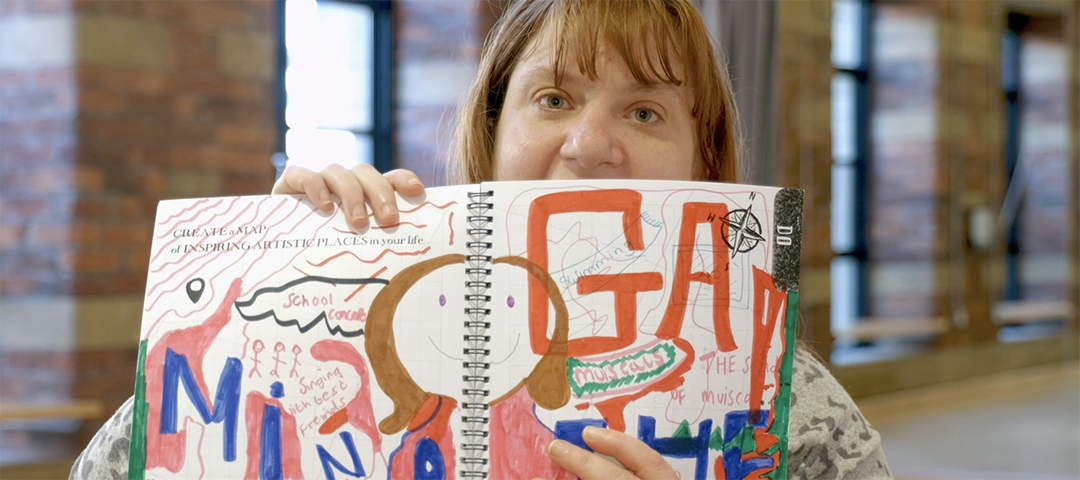

By Professor Matthew Reason, Principal Investigator of the ‘Creative Doodle Book’ project. The Creative Doodle Book project is a collaboration between Matthew Reason of York St John University, learning disability arts company Mind the Gap and Vicky Ackroyd of Totally Inclusive People.

A recurring feature of the UK government’s guidance during Covid-19 concerned ‘shielding,’ giving advice for people identified as clinically vulnerable from coronavirus to stay at home and self-isolate. This included many people with a learning disability or autism, such as adults with Downs syndrome.[1] This guidance was accompanied with recognition that, as well as being more vulnerable, people with learning disabilities may also require more support in understanding restrictions and managing changes to their lifestyle.[2]

Despite such measures – or more accurately, according to the Health Foundation, because the support provided to enable the measures was inadequate – 6 out of 10 people who died from Covid-19 in the UK have been disabled.[3] Figures from Mencap suggest that people with a learning disability have died from Covid ‘at up to six times the rate of the general population.’[4]

If the most predominant presence of disabled people during Covid-19 in the UK was in terms of statements of their vulnerability, then the second most prominent presence was an absence. This time in the form of a lack of BSL provision during official governmental briefings.[5] First raised in Spring 2020, in July 2021 a court judgement ruled that the government had acted illegally in not making broadcasts accessible to d/Deaf people.[6]

These two elements together – a labelling of vulnerability accompanied by a neglect of attention to actual needs – is an attitude that is at once paternalistic and careless. It positions disabled people as objects, rather than agents, in their relationship to their own lives. In 2007 Medcap published their Death by Indifference report, which described failures in health provision for people with learning disabilities that resulted, in no small part, from a failure to listen to their own articulation of their needs and experiences.[7] While wrapped up in language of ‘shielding’ and ‘vulnerability’, responses to Covid-19 repeated this failure to listen to actual experiences. Well into the twentieth-first century were found ourselves somehow returned, both symbolically and practically, to the long history in which (as Petra Kuppers articulates it) disabled people are at once hyper-visible as objects of interest or concern, yet invisible as active members of public life through their own voices and perspectives.[8]

Agency through the Arts

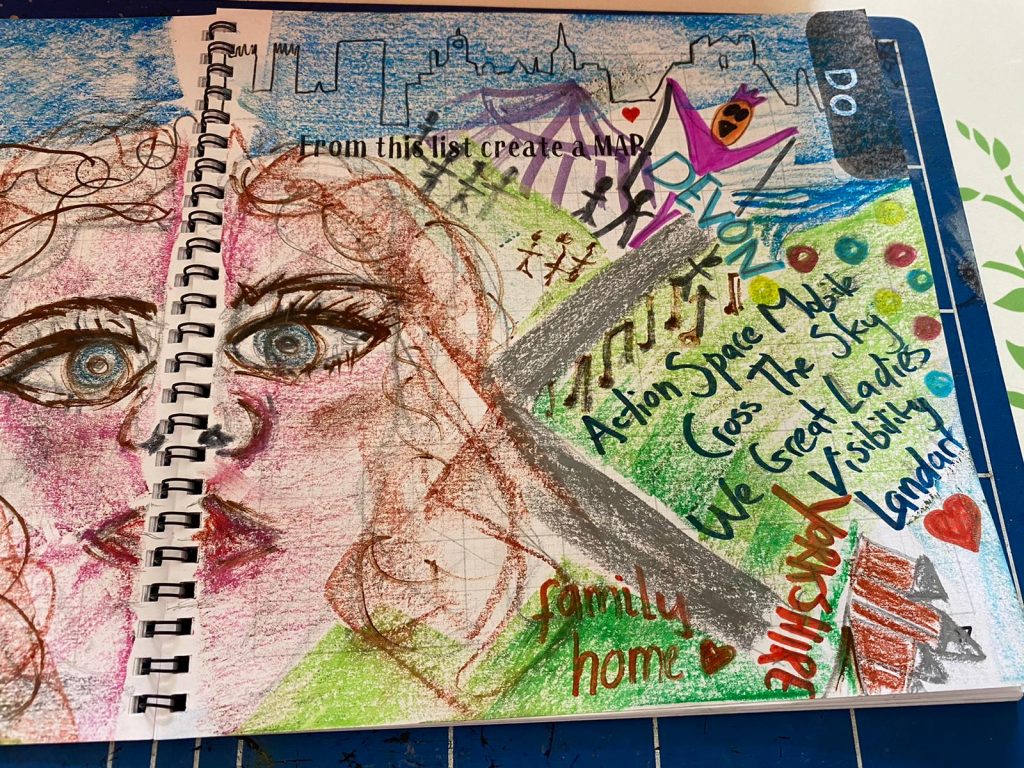

The Creative Doodle Book project, funded by the UKRI as part of the Covid-19 Rapid Response call, involved delivering participatory arts practice to 20 organisations across the country working with people with learning disabilities and autism.[9] This included SEND units within schools and self-advocacy groups (such as Bradford People First), but the majority were arts groups. As part of the project we interviewed practitioners and participants from these groups, collecting their Covid stories and discovering how many organisations had rapidly pivoted to different forms of remote, online and doorstop delivery. As we did so a picture emerged about the importance of the participatory arts as a ‘lifeline’ to their members, a space in which to connect, to escape, and a rare opportunity to feel listened to.

This potential was articulated powerfully by Alice Linnane, creative producer with Kent-based Square Pegs, who run theatre and art groups for young people and adults with learning disabilities.[10] In our conversation Linnane observed that:

There is a real narrative where my company members are told all the time by the world around them that they are vulnerable and they need looking after. And that they don’t understand, or things aren’t for them. It’s a very patronising world that neurodivergent people live in.

These creative spaces are an opportunity to challenge some of that, and for them to feel valuable and important, that their voice matters, and that they get to have one. […] They have a really unique perspective on the world and that that perspective should be explored and shown in the same way that all of the rest of people’s lived experiences are.

Similar comments were made by other groups. Jenna Howlett of Fuse Theatre, who work with young people with learning disabilities in North Yorkshire, asserted that ‘Creativity comes with having your own voice and you’re heard.’[11] While Claire Reda of Glasgow-based Indepen-dance stressed the importance of providing opportunities for self-expression: ‘I definitely sense that there was like a real need for everyone to do that. Like just kind of communicating that they’re here and they have a voice.’[12] Remarks such as these accumulated through our project, along with discussion of how the Creative Doodle Book enabled a ‘reflective space’ to explore the world and our place within it.

The value of these conversations, and that sense of having a voice, should not be underestimated. It provides an emotional outlet and sense of agency that supports wellbeing in all sorts of important ways. For Laura Bassanger of Starlight Arts, the Creative Doodle Book gave the company members a space ‘to be able to express themselves and how they were feeling at that time or what had been going on now. […] It was just a real empowering, positive experience for them.’[13]

In the context of the alienating and disempowering experiences of lockdown and social distancing, the work of participatory arts groups in enabling such creative expression is an invaluable mental health provision. Moreover, it fulfils a basic human need for self-expression. However, while vital on an individual and community level, it does not change that more macro-picture. Beyond the virtual Zoom-room in which they were expressed, these voices and these perspectives of people with learning disabilities remained unheard.

One of the values of the participatory arts is its ability to provide an articulate and powerful vehicle for the voices of individuals and groups that are under-represented within public life. An example of this is when Newham-based company Act Up! produced a video documentation of their engagement with the Doodle Book. This provided a window into experience, powerfully presenting something of the lockdown perspectives of people with learning disabilities.[14] Nonetheless it is hard to avoid the painful feeling that Covid-19 is a testimony of just how fragile movements towards greater disability rights remain. The governmental response to the pandemic is an extreme example of how, as described by the social model of disability, it is society that disables through its neglect of adequate support, accessibility and – just as importantly – agency. The right to be heard within public discourse, particularly public discourses about something as unprecedented as Covid-19, should be a fundamental right.

[1] https://www.downs-syndrome.org.uk/about-downs-syndrome/health-and-wellbeing/coronavirus-covid-19/

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-supporting-adults-with-learning-disabilities-and-autistic-adults/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-for-care-staff-supporting-adults-with-learning-disabilities-and-autistic-adults

[3] https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/news/6-out-of-10-people-who-have-died-from-covid-19-are-disabled

[4] https://www.mencap.org.uk/press-release/mencap-comments-latest-shielding-guidance-and-calls-all-people-learning-disability

[5] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-54400857

https://www.disabilityrightsuk.org/news/2020/december/vital-covid-information-inaccessible-bsl-users

[6] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-leeds-57998047

[7] https://www.mencap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2016-06/DBIreport.pdf

[8] Petra Kuppers Disability and Contemporary Performance. 2003: 49

[9] https://www.mind-the-gap.org.uk/project/creative-doodle-book/

[10] https://squarepegsarts.com/

[11] https://fusetheatre.wordpress.com/

[12] https://www.indepen-dance.org.uk/